by Rob DiCristino

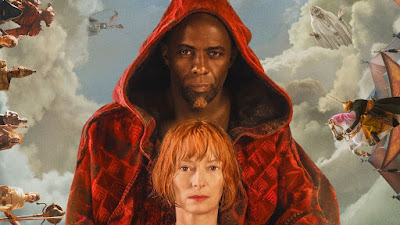

…for a shirtless Idris Elba.In George Miller’s long-awaited follow-up to Mad Max: Fury Road, Tilda Swinton plays Dr. Alithea Binnie, a narratologist. No, she didn’t make that up. It’s a real thing, apparently, a field of academic study that turns a Joseph Campbell-sized lens toward the world’s cultural traditions, analyzing story structure and looking for commonalities in characters and themes. This is a Cool Job, and despite Alithea’s gawky bookishness, she’s a Cool Lady. While in Istanbul for a conference, Alithea is drawn to a mysterious blue bottle from which, after a series of innocuous polishes, suddenly bursts a gigantic Djinn (Idris Elba)! You know where this is going: After shrinking down to a more relatable size, the Djinn offers Alithea three wishes. The usual rules apply, of course — no resurrections, etc. — but Alithea has read far too many cautionary tales to fall for a trickster’s trap. She challenges the Djinn to prove his benevolence before agreeing to make the wishes that will free him from his captivity. To do so, the Djinn recounts tales of adventure that led him to Alithea’s service.And so, in the latest film from one of our most celebrated visual auteurs, two of the most striking, dynamic actors in Hollywood don scratchy hotel bathrobes and settle down for a nice, long chat. The Djinn catalogs his titular years in the courts of ancient kings, his love affairs with beautiful empresses, and the twists of fate that have kept him in captivity for so long. It seems that his affections have been his undoing, that he misplaced his belief in the eternal love of women whose great sins were being flighty, mercurial human beings. Far from the boasting, whimsical figures of other genie tales, this Djinn is remorseful and introverted, constantly examining his own mistakes and sharing his hard-earned wisdom with the lonely Alithea. For her part, Alithea uses the Djinn’s stories as further proof of the benefits of solitude. Her only marriage fell apart years ago, and she’s focused the subsequent time on her work. Though she remains icy and logical throughout, Alithea taps this experience to sympathize with the Djinn’s pain, confusion, and hopelessness.

Adapted from the stories by A.S. Byatt, Three Thousand Years of Longing hums along with wit and charm for the first two-thirds of its runtime. George Miller hasn’t lost a creative step; his lush production design and now-famously pristine staging and cinematography return with all the verve of a maestro who’s had nearly a decade to recharge his creative batteries. Though there are few speaking parts outside of our two leads, Miller and his team use such a striking and varied palette of warriors, courtesans, royals, and mystics that each of the Djinn’s tales stands out in its own unique way. Idris Elba is glorious in the role, his signature baritone somehow even warmer and more thoughtful than usual. Tilda Swinton plays a wonderful skeptic, a romantic whose heart has been bruised far too many times to leave out in the open. She shocks the Djinn by revealing that she wishes for nothing: She is self-sufficient, successful in her work, and (she believes) personally fulfilled. All Djinn stories end poorly, Alithea tells her companion, so there’s no reason to tempt fate.

Had the film held close to this initial premise — a ruminating chamber drama with long interstitials of time-traveling fantasy — Miller might have had another masterpiece on his hands. Instead, his final act shifts gears to the future, where our leads have entered into an odd domestic arrangement that raises more questions than it answers. We’re left to ponder the greater meaning of the preceding acts, to wonder what exactly we learned about love, fate, and desire. For a film so interested in narrative, Longing can’t seem to come to a coherent conclusion about this one. It’s even more frustrating when we consider Alithea’s opening lecture on the evolutionary purpose of storytelling: Now that we've harnessed technology (cell phones, penicillin, etc.), do we really need to speculate and wonder as we once did? Do we need fairy tales and allegories to teach us right from wrong? Longing keeps pawing at these ideas without deciding exactly what we’re meant to take from them. This is okay! It’s just hard to square with Miller’s otherwise precise and elegant craftsmanship.

But then again, maybe it’s this lack of a definitive catharsis that makes the scrappy Three Thousand Years of Longing more than the sum of its parts. It’s a romance, after all, and every great romance has its ambiguities. What’s for certain is that Miller took a wonderful risk by returning from his hiatus with a contemplative character piece rather than leveraging his Mad Max clout into a summer tentpole gig with Marvel or Star Wars. It’s a win for those cineastes who will happily stomach some of Longing’s more underwhelming movements in exchange for a surefire Film Twitter-friendly top ten entry come year’s end. I’m not entirely convinced it’s earned that, but I cannot argue with the relief of seeing Miller back on our big screens with an ambitious film that does earn the effort of its other talented creatives. Maybe “uneven but insightful” is better than the tepid gloss of the latest Jurassic World or Spider-Man entries. Truth is, I’ve given up speculating about how audiences will respond to things. I just don’t know. But then, none of us do. It’s up to the stories to teach us, isn’t it?

No comments:

Post a Comment