Week Seven: The Elephant Man

Rob: Welcome to Weird on Top, where the stars turn and a time presents itself. I’m Rob DiCristino.

Alejandra: And I’m Alejandra Gonzalez.

Rob: This week, we’re flashing back to 1980 to discuss David Lynch’s first major studio effort, The Elephant Man. Based on the real-life medical memoir The Elephant Man and Other Reminiscences (and co-produced without credit by comedy legend Mel Brooks, who didn’t want to confuse audiences by putting his name on a drama), the film follows Victorian-era (era) doctor Frederick Treves’ (Anthony Hopkins) discovery and rehabilitation of the horribly disfigured street performer known to East End audiences as “The Elephant Man” (John Hurt as John Merrick). Though Merrick’s lumpy, swollen features and unsettling demeanor horrify the hospital staff and earn Treves the ire of his boss (John Gielgud as Mr. Carr-Gomm), the young doctor believes that he can heal Merrick’s soul (if not his body) with the kind of sympathy, kindness, and dignity that has been denied him his entire life.

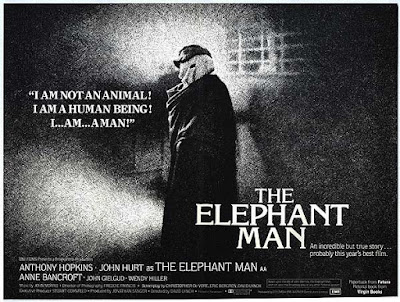

At first thought to be a risky and unsellable project, The Elephant Man was a triumphant commercial and critical success that announced David Lynch to mainstream audiences in the same way that Eraserhead had to the midnight grindhouses just a few years earlier. It was nominated for Golden Globes, BAFTAs, and Oscars galore, winning several and eventually inspiring the Academy to create an award for Best Makeup and Hairstyling. Merrick’s climactic line, “I am not an animal! I am a human being! I am a man!” has also endured as one of the more recognizable in recent film history. Perhaps most significantly, The Elephant Man briefly made Lynch a hot Hollywood property (he famously turned down George Lucas’ offer to direct Return of the Jedi the same year), and he would build on the film’s success with a larger, bigger-budgeted, more ambitious project: 1984’s Dune. We’ll...get to that later.

I’ve always thought of The Elephant Man as a well-constructed prestige picture that — though the subject matter is decidedly Lynchian — could have more or less been made by any director worth their salt. It’s elegant and beautiful. It’s got big, important British actors and gorgeous black and white photography by Hammer alum Freddie Francis. It’s a heartbreaking examination of the human condition, and so on, and so on. I like it lot, but I never considered it one of Lynch’s best. However, rewatching it so soon after Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me allowed me to focus on Merrick’s story as one of emotional abuse, a Laura Palmer-esque search for agency and personhood that goes beyond coping with physical deformities, and that endeared me to the film quite a bit more than I had been before. It’s a sentimental and surprisingly timid entry in Lynch’s canon (definitely not the kind of thing he’d make today), but it fits in comfortably enough.

Ale, what are your thoughts on The Elephant Man?

Alejandra: Not unlike the other movies we’ve covered so far, I hardly know where to begin with The Elephant Man because I’m still not sure exactly how I feel about it. On one hand, I think it’s incredibly moving and well done, but I agree with you in that this could pretty much have been made by any director who knew what they were doing. I’ve heard it said that The Straight Story is the biggest outlier in Lynch’s work, but I would argue that The Elephant Man is the real deviation from what we assume is standard for David Lynch. I kept waiting for something really unusual to happen, but the closest we get to that is a nightmare sequence where John sees himself in a mirror and then his dream before he dies. I don’t mean to sound as if this is criticism against the film because, as you mentioned, its success did allow for Lynch’s introduction to a much wider audience. In fact, I found myself thinking a lot about Disney’s The Hunchback of Notre Dame watching this, as it concerns itself with similar themes and almost takes things directly from The Elephant Man, such as Quasimodo’s affinity for building miniatures of the city he is kept from. If a powerhouse like Disney really did take direct inspiration from The Elephant Man, it would be a testament to just how commercially successful and influential it was.

It’s also a story that is equally heartwarming as it is heartbreaking. Your comparison of John to Laura Palmer is incredibly apt, because I don’t think The Elephant Man is so much about deceptive appearances and skin-deep beauty as it is about the tragedy that occurs when one loses autonomy over themselves. I find that despite his death at the end, his choice to finally lay down to sleep, even understanding the dangers of doing so, was John’s way of reclaiming this autonomy. I’ll be honest: this is an incredibly difficult watch for me because of a few reasons. First of all, having been completely traumatized after my viewing of 1932’s Freaks at a relatively young age, anything that concerns itself with carnivals or circuses is absolutely nightmare fuel for me. It took some introspection to realize that this was because I knew that these characters were not in makeup and that this was for real. It’s not something I’m proud of at all, but If I’m being completely transparent with myself and anyone reading this, I think the same applies to The Elephant Man. I knew this was based on a true story, and having to see John felt uncomfortable and unpleasant because I felt so much guilt. I think that’s one of the things this film does so well, though. When you’re watching, you are angry at the way John’s visitors react to his appearance, but then you realize that perhaps you aren’t much different. Maybe I’m just speaking for myself, but do you know what I mean?

Rob: Oh, absolutely, and I think that ability to really identify with the leering crowds is key to our understanding of what Merrick is going through. Judging by his avoidance of mirrors, we can tell that even he finds himself to be abominable. It’s painful and wrong, but it’s human. One thing I noticed this time — and one thing that critics often cite as a flaw in the film, but that I see as intentional — is Merrick’s inability to speak until provoked by his failed interview with Carr-Gomm. That’s where the emotional abuse angle really kicked into gear for me, as victims of that kind usually lose self-expression in even that most literal of senses. It takes an extended stay in a safe environment for Merrick to feel confident enough to speak. He’s probably been internalizing the hate and shame you described for so long that he stopped thinking of himself as a human, which makes that “I am not an animal!” line so cathartic. He’s not just asserting his personhood to the angry crowd, but to himself.

Speaking of which, I have to give this rewatch credit for making that scene in the theater — the one where Merrick stands to acknowledge a cheering audience full of wealthy and royal Londoners — work for me in a way it never has before. It’s cheesy and melodramatic, for sure, but consider how much of a departure it is from Merrick’s experience up until that point: Rather than a curtain pulling back to reveal a throng of drunken, angry patrons who want to revel in Merrick’s misery — or, it has to be said, a team of medical scientists poking and prodding at his genitals like he’s a lab rat— he’s given the opportunity to stand up and finally assert his humanity and dignity to people who want to celebrate him for those things, and for those things only. It’s the context of the cheers and applause that finally push him to complete his chapel project (which we could read as reaffirming a belief in God or spiritual salvation) and laying down to die peacefully, cathartically, and completely sure of his own worth.

What did you think of Anthony Hopkins’ performance as Treves and the character overall? I find it to be a bit of a weak spot. His initial motivation for studying Merrick makes enough sense — a young, hot-shot doctor trying to make a name for himself. But I’m not sure I sense where and how his character really arcs into a more sympathetic perspective, or if he ever even needed to. He seems a decent man from the start who stays decent throughout. I’m not necessarily saying there’s a problem in the construction of his character, really, or that every character needs to have an obvious arc. I just had a hard time pinning down exactly who he is and what he wants. There’s that one scene where he has his little moral crisis, but what really changed afterward? He’s such a crucial force in Merrick’s rehabilitation, but how much do we get to see of his own struggles? I don’t know. I just felt the whole thing was a bit thin.

Alejandra: While I definitely agree with you that nothing really changes after his crisis, I actually really like what the character brings to the story. He was right in wondering if he was just like Bytes, because for the entire first half of the movie I would have agreed that he was, only in a less obvious way. It was clear that Treves’ main motivation in helping Merrick was to impress the community, but I would even say that he was doing it to prove his moral superiority to himself and others, which ends up not being very moral at all. This may be a reach, but it made me think about men who claim to be allies to women who underneath such public efforts to look good aren’t allies to us at all. I really love the scene where he is talking to one of the nurses and she accuses him of showcasing Merrick in the same way that Bytes does, and upon losing him, Treves feels immense guilt but not much of anything else in the latter half. I think Treves simply wants to feel like a noble man, and people might disagree with me when I say that I don’t think he ever really saw John as a friend or whole person at all. It was devastating for me to see John affectionately call Treves his friend so often with Treves never really reciprocating. What I like about that is that The Elephant Man says a lot about what it takes to be truly compassionate and empathetic. While I think Treves helped John tremendously, I don’t think he ever truly wanted to if not for reasons that were a little selfish. I by no means believe that Treves was an awful person, and maybe I’m being harsh. I just don’t think Treves ever meant to help John restore his independence. In fact, it feels as if he wanted just as badly as Bytes to keep John in his own possession. The only person who sees John for who he is is Mrs. Kendal, who we should have seen with John more often.

Rob: I agree with a lot of what you’re saying, and I think you hit the nail on the head as to a lot of my issues with him. I think we’re meant to identify with Treves, as well, but I would have been able to do that if I saw more of a fluctuation or dynamism in his character. For example, there’s a debate about “incurability,” the idea that a hospital has no business committing resources to someone they cannot hope to make better. The Princess Alexandra (Helen Ryan) scene diffuses that situation, but I would have preferred to see that thread explored with a little more nuance by characters I already knew, like Treves. It’s just a minor thing, but as long as we’re nitpicking.

Alejandra: Oh boy, it sounds like I liked this movie a lot less than I actually did. All of these criticisms aside, there is a lot to learn from John Merrick’s story as told by Lynch. Some of the greatest parts of the film were the ones where we saw John by himself or the scenes where we learn more about him. I loved listening to him talk about his mother with the people Treves introduces him to, and I loved listening to him talk about the miniature sculptures he builds, and how he read the bible daily. All of these things made John who he was — not what he looked like or the way he was treated by other people. Any other thoughts on The Elephant Man?

Rob: Just to say that I think it’s a good movie that could have been great if Lynch had the freedom to be himself and build on the tone and style he’d established with Eraserhead. I don’t know if he was under pressure to keep things commercial, but I imagine he was nervous about working on a “real” movie for the first time and trying to keep it palatable for his producers at Brooksfilms (especially considering it was one of their very first productions). This is no knock against those producers, of course; we all know what can go wrong when a young, confident hotshot gets carte blanche to do whatever they want. All I’m saying is that The Elephant Man feels like David Lynch on probation, and he might have made something truly fucked-up and memorable had he taken this on later in his career.

Alejandra: All in all, I really enjoyed and appreciated The Elephant Man, this time more than ever despite the fact that it is still incredibly difficult for me to watch. It’s not exactly an upper, and I’m not sure Lynch actually has many of those, but The Elephant Man remains one of his most distressing films. I feel like had this film come out of any other filmmaker’s oeuvre it would be somewhere at the top of the ranking of their work, but because it’s Lynch, I always forget it even exists. Again, that does no favors for my case of actually really enjoying this film, but it’s very true for me.

Rob: We’ll be back next time to talk about this column’s namesake, 1990’s Wild at Heart. That’s right: We’re about to get our Cage on. Until then, remember: This world is wild at heart…

Alejandra: And weird on top.

No comments:

Post a Comment